Capital at risk. Interpretation of the latest rates may require the excellent knowledge of the financial trades as it could be beneficial. The original investment amount may not be returned to investors.

There has been a clear relationship between energy demand and economic growth for some time. Demand for energy grows as economic activity picks up. Energy use is lessened during periods of recession. This very simple equation has loomed over energy markets for the past few months. The global economy is faltering, so energy demand will probably diminish.

In reality, the dynamic is far more nuanced. The world economy is weakening, and that’ll be negative for energy demand. That said, this must be framed against a longer-term upward trajectory in energy consumption. Energy demand is now above where it stood before the pandemic, having returned to its multi-decade trend in 2021. At the same time, European governments are looking to stockpile energy resources (especially oil and gas), which is supporting demand.

But the real support for energy prices is coming from the supply side. Supply is still constrained not just because of the war in Ukraine but because of longer-term considerations. Energy companies have been nervous about capital expenditure, with the uncertain near-term payoffs of bringing on new fossil fuel supply in the context of the energy transition. Governments have lifted some restrictions on additional supply, but creating that new supply will take time.

Simultaneously, any stirrings of a near-term supply increase by would-be alternatives, such as OPEC, are downright fanciful. The consortium has agreed to a minor increase in production, about 100,000 barrels a day. Still, its output is running roughly two million barrels a day short of the levels of spring 2020. Oil-importing nations have reached out to boost supply but have been turned away.

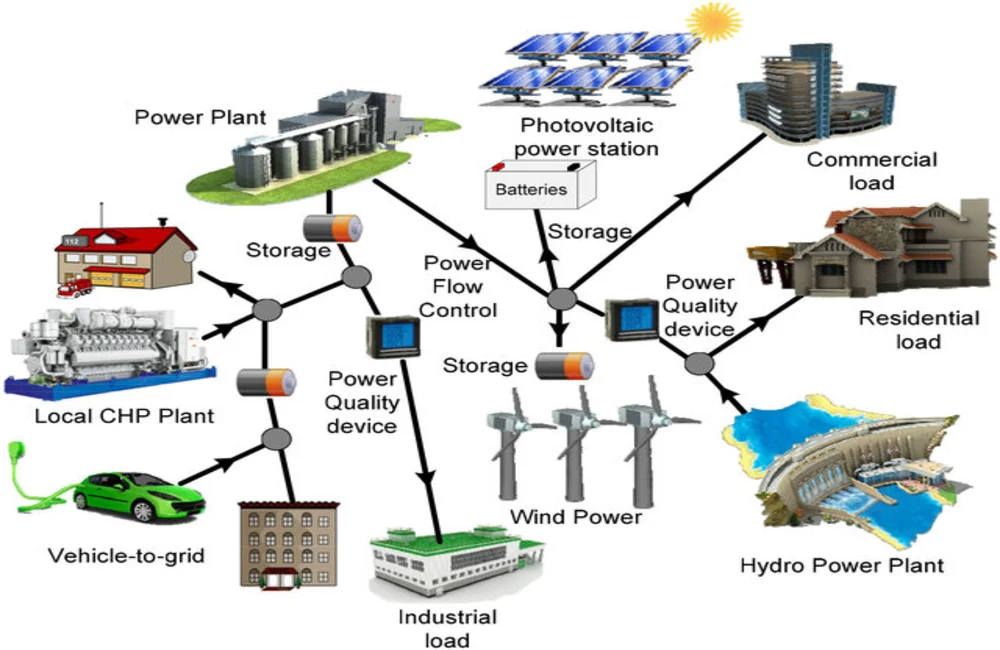

A shift in the energy mix

In all of this, we still see an environment for energy when balancing supply vs. demand as favourable. But the energy mix is sure to shift. In the immediate term, governments are seeking quick solutions to the disruption of Russian supplies. Member states of the Eurozone, for example, have committed to reducing gas demand by 15%.

Germany and France have reached an agreement for an energy swap, in which Germany will supply France with electricity and France will provide Germany with gas in the case of shortages. And the EU is also discussing some short-term support for coal. In the UK, Liz Truss’s incoming government passed out new oil and gas exploration licences and removed the moratorium on fracking for shale gas.

Over the longer term, governments are looking to achieve greater energy independence, a trend that will drive the transition to renewables. A major push for solar and wind power investment is included in Europe’s €210bn package to lessen dependence on Russian fossil fuels. The European Commission is now aiming for 45% of its energy mix to come from renewables by 2030. As for the UK, Prime Minister Truss says there will be investment in new sources of energy supply, including nuclear, wind, and solar.

A change in thinking

The Ukraine crisis has led to a broader and sobering re-evaluation by investors generally of the facts of the energy transition, and the part that fossil fuels must play in the short term. “Climate risk is investment risk,” argued BlackRock chief executive Larry Fink in his 2020 annual letter to CEOs, and he has noted that “the importance of sustainability to investment returns is only increasing, and we believe sustainable investing is the strongest foundation for client portfolios in the future.”

That is certainly true, but he also noted: “divesting from entire sectors — or even just passing carbon-intensive assets from public markets to private markets — will not get the world to net zero.” In it, he writes that “companies need to ensure that people still have access to reliable and affordable energy sources. It is the only way to build a green economy that is equitable, just, and free from the fractures that can arise whenever people are pitted against one another. Any such supply-only focused plan, which doesn’t seek to curtail demand for hydrocarbons, would increase energy prices for all but those who can least bear the cost, further polarising climate change in politics and undoing progress.”

The Ukraine crisis has brought the complexities of the global sourcing and use of energy into sharp focus. This is also why we think it’s so crucial to have exposure to the energy sector holistically and to be able to tactically allocate across the continuum. Demand is holding firm, but supply remains constrained; however, the world’s energy mix will never stop shifting. On this front, it is this uncertainty that logically necessitates a fully flexible energy transition, which is why we undertook changes in the Trusts’ holdings in 2020 to help it embrace the full spectrum of old and new energy.